|

Bulletin of Applied Computing and Information Technology |

Making Research Work for You:

|

|

Quantitative |

Qualitative |

|

Software Metrics |

Usability tTsting and System Trials |

|

System Performance |

Interviews – Delphi and Q Methodology |

|

Capacity Testing |

Content and Discourse Analysis |

|

User Surveys |

Ethnographic Studies |

|

Questionnaires |

Case Study Method |

Table 1. Research method domains & associated instruments

For research into professional practice, an action research model is useful, as discussed later.

A lot of research methods are said to be from the social sciences rather than the hypothesis testing of scientific methods. So now it gets very hard to decide which way to turn. In IT we can build our research methods by looking both inwards and outwards at the 'things we do'. This is where the review of the literature is handy to move you towards focusing and developing some key questions and a problem.

Some basic planning steps to follow were made aware to me at a thesis writing workshop (Eustace & Dunn, 1999). It is important to start by writing a list called the 'Project Data' Template(Figure 1) that:

Identifies the core activities

Determines their logic and sequence

Reveals a time management plan

Estimates the time and resources required – economies of scale

Present your this list or plan to others: supervisors, peers

|

Project Data Template |

|

Project Title |

|

Start Date |

|

Finish Date |

|

Equipment |

|

Background/Prior kKnowledge |

|

Technology |

|

Other Contributors Background/Prior Technology: |

Figure 1. Project data form as a template to shape ideas

The project data form (Figure 1) is used to develop a project proposal plan to present to your supervisors and colleagues. If your study involves human participants, it is vital when planning the methodology that you conform to the ethical guidelines for that research. All dissertation proposals are screened for ethical approval prior to acceptance; although as a research thesis student you should have at least considered these issues before writing and submitting the proposal. A well considered proposal plan (Figure 2) is likely to win you praise from your supervisors. The ethical guidelines are a big help in finalising the research design, methodology, instruments used to collect the data and how it will be processed, communicated and stored.

|

The Research Proposal Template |

|

Project title |

|

Problem Domain and Key Question(s) |

|

Project Objectives |

|

Relevance to Honours or Postgraduate degree |

|

Methodology |

|

Expected Outputs & Outcomes |

|

Milestones |

|

Cooperative Linkages |

|

Risk Management |

|

Communication |

|

Commercialisation Strategy |

|

References |

Figure 2. Research proposal plan template

A research student has to undertake two crucial activities, in a 'to' and 'from' manner:

Forward schedule: start the activities on a given date and carry them forward to the finish date.

Backward schedule: look at the date when the thesis is due and work out the logic and start dates of activities backwards.

Try to reduce the amount of multi-tasking ('bad multi-tasking') in your work. Imagine you have three tasks to do at the same time:

A: your literature review;

B: technical assignment; and,

C: essay on research methods.

Here is a short example of the impact of bad multi-tasking (Figure 3):

Figure 3. Example of bad multi-tasking.

Assume each task took 10 days. If you do them in sequence, then the lead-time from start to finish is about 30 days. If each of these tasks was broken into 2 smaller units of work, by doing half of each before returning later to finish off each second half, then the effect of such “multi-tasking” is to make each project LONGER than they needed to be.

The time constraints are the START and FINISH dates for each activity. This can be entered into a Microsoft Project plan or on paper using an * for each week.

Let me assume that you start on Monday 02 February, 2004 and finish on Monday 08 November. [You will learn to like “Mondays” for your project milestones]. That means that your thesis year is about 39 weeks long; for a PhD, multiply by 3 (Table 2 and Table 3).

| Activity | Time Constraints | Weeks (*) |

|

Project start date |

02/02 - |

|

|

1 Generate potential topics |

02/02 - 15/03 |

******(6) |

|

2 Carry out literature review |

01/03 - 16/05 |

*********(9) |

|

3 Finalise topic |

17/05 - 24/05 |

*(1) |

|

4 Design study |

17/05 - 31/05 |

**(2) |

|

5 Prepare materials |

31/05 - 21/06 |

***(3) |

|

6 Gather data |

21/06 - 26/07 |

*****(5) |

|

7 Analyse data |

02/08 - 30/08 |

****(4) |

|

8 Write-up |

30/08 - 27/09 |

****(4) |

|

9 Revise and edit |

27/09 - 01/11 |

*****(5) |

|

10 Submit dissertation |

- 08/11 |

|

Table 2. Interim activity planning

|

|

Feb. |

Mar. |

Apr. |

May. |

Jun. |

Jul. |

Aug. |

Sep. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

|

1 Potential topics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 Literature review |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 Finalise topic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Design study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 Prepare materials |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 Gather data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Analyse data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 Write-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 Revise and edit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 Submit dissertation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Interim project plan in graphical form.

The plan is revised and running well by the start of 'June' (the metaphorical halfway point) and has changed shape due to the impact of the research methodology and the choice of quantitative and qualitative tools. The use of a questionnaire in my example, could readily be substituted by a range of information systems research methods, such the use of interviews, case study method, field work, ethnographic techniques etc. The revised plan is likely to reveal how a bottleneck brings back potential for 'bad multi-tasking' during 'September' (the 75% stage of the thesis). Write-up, revision and edit, as well as the submission, are kept clear and on track, as you work to the finish line with your supervisors (Table 4 and Table 5).

|

Activity |

Time |

|

Project revision date |

06/06 |

|

1 Update literature review |

16/06 |

|

2 Arrange visits |

30/06 |

|

3 Prepare questionnaire |

25/07 |

|

4 Review questionnaire |

08/08 |

|

5 Deliver questionnaire |

26/09 |

|

6 Analyse results |

31/08 |

|

7 Write-up |

30/09 |

|

8 Revise and edit |

31/10 |

|

9 Submit dissertation |

08/11 |

Table 4. Revised activity planning in 'June'

|

|

Jun. |

Jul. |

Aug. |

Sep. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

|

1 Update literature review |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 Arrange visits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 Prepare questionnaire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Review questionnaire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 Deliver questionnaire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 Analyse results |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Write-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 Revise and edit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 Submit dissertation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5. 'June' revised project plan in graphical form

Computing and information technology students are not renown for their oral and written communication skills, when compared to other fields like science and education. This section is designed to help improve the writing skills needed for a thesis. In discussing the management of the writing process, Brown (1995) provides a solid discussion point relating to the twin issues of the big picture and the big question by stressing the need for:

continued direction;

deliberate management using top-down methods;

creation of clarity;

a grammar focus;

a hierarchy of tasks vs. questions;

the essence of management as self-determined;

an ability to manage time and fear;

combining the suspense format and the journalist pyramid form of writing.

Top-down management is an approach which leads to the final breakdown of the writing process, beginning with the big question, into the basic level 6 unit called the sentence:

Big question

Subsidiary questions

Chapters

Sections

Paragraphs

Sentence

The sentences should be simple, short and sharp as simplified prose is better and is always clearly thought out. You need to begin writing the day you begin your thesis. Reading out aloud is a good way to refine your thoughts and helps to build your associative memory skills. There is often an early inertia as feelings about lacking knowledge can stop you from starting to write, so consider the following advice: "You don't know what you don't know until you start writing"

The management of the writing process should develop a feel for synchronised research and writing, so try not to separate either part of your thesis. This method is an object modelling process, where each thesis object is modelled to assist in developing cohesion. Some objects in the thesis structure for definition and linking are:

Thesis

Acknowledgement

Table of Contents

Chapter

Introduction

Heading level

Paragraph

Sentence

Footnote

Citation

Figure

Table

Literature review

Question hierarchy

Theoretical/practical framework

Research design

Methodology

Raw data

Analysis of data

Results

Conclusion

References

Appendix

In tabulated summary the linkages can be made vertically and horizontally in Table 6.

|

title |

footnote |

research design |

|

acknowledgement |

figure (graph/diagram) |

methodology |

|

table of contents |

table |

raw data |

|

introduction |

citation |

analysis of data |

|

chapter |

literature review |

results |

|

heading level |

question hierarchy |

conclusion |

|

paragraph |

theoretical framework |

references |

|

sentence |

practical framework |

appendix |

Table 6. Defining and linking objects in the thesis structure

Robertson (1999) suggests that thesis writing must provide a well structured and up-to-date review of the literature. This section examines the why? what? and how? of writing a critical literature review.

|

For the project: |

To find evidence and to establish the need for your project. |

|

For yourself: |

To continue the process of learning and research that will continue throughout your academic life. |

|

For the examiners: |

To establish your professional

competence; |

Table 7. Some reasons for doing a critical review of the literature

You are writing for the project, for yourself and for your examiner(s). For the project under investigation, a critical literature review helps to find evidence for the need for the project or investigation such as filling a major gap in knowledge. Since the literature review is a continuous process, it does require a disciplined organization and helps the writer to track resources and to read critically, discover methodologies and to build a research design . Finally, the examiner looks for your professional competence in the topic area in both depth and breadth. It is important to use the literature review to build the theoretical and practical frameworks or context for the study. The examiner has to be convinced that the project is justified (Table 7).

One way of answering this is to describe a literature review as having five features:

Breadth

Shape

Logical flow

Detail - General

Primary literature

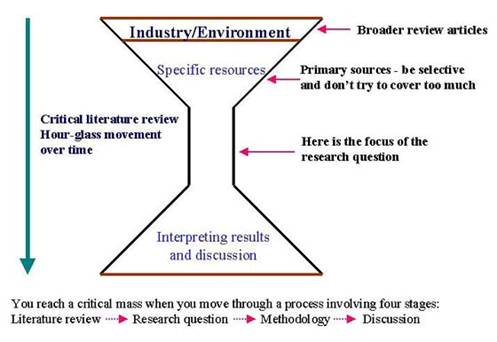

Sometimes a gap appears in the literature. That gap may contain your research agenda and point you in the right direction, so do not ignore the worth of the literature review. The researcher’s 'hour-glass' model (Figure 4.) is useful in helping to see the process and functions, together with its connections to other stages in the development of your thesis, that the review of the literature helps to reveal.

Figure 4. The hourglass model for shaping the research process

Overall the literature review has an hour-glass shape. At the top it begins with broad context literature that shows where the research fits into the industry, discipline on environmental context. Then it narrows or spirals down to primary literature relevant to the problem itself. This stage also exposes knowledge deficiencies and justifies your research. At this stage you must exhibit a grasp of the significant literature and knowledge gaps which your thesis will address.

Your research project takes place at the narrow waist of the hour-glass after which the story 'widens out' again showing the results, interpretation, discussion and conclusion. At this stage you should return to the 'big' question. Keep the literature review short and show only major and significant references. Fifty pages of references are too much!

Start with the broad literature on your topic - there is no need for primary critical literature - but you get down to your 'big question' about a specific topic. Then you need to go on to the seminal and primary literature to establish the knowledge gaps, where you will work. Learn to work the gaps.

This is often asked and the immediate answer that is often used includes peer reviewed articles, however the theses of other students before you, are also quite valuable.

It describes, summarizes, evaluates, clarifies, integrates, synthesizes, informs and targets - i.e. takes the reader somewhere on their thesis journey. Be aware that the literature does not list, regurgitate, confuse or ramble.

Sources include your supervisors, library, Internet (Web sites, chat groups (e-mail, newsgroups and Web bulletin boards), experts, conferences and workshops (like the one that spawned this paper!). At this stage, you must realize that the supervisors are reaching their 'used-by dates', because in most fields, the literature is so vast, for example, agriculture or the agenda is volatile and changing rapidly e.g. information technology research. The supervisor's most useful role is in quality control – for example, to help you to throw away a lot of irrelevant literature and to introduce you to the experts in the field. A good idea is to take your supervisor to conferences so that they can introduce you to the experts, or you should try to find and participate with an e-mail discussion group to filter your references and to develop your methods.

This must have:

a beginning - broad scope

a middle - details

an end - conclusion

Use a check list containing when proof reading is done by you and by others:

focus - is it clear?

goals

perspective - is a new reader able to follow?

coverage - detail

organization - is it clear and logically presented?

Make a list of goals and write a topic or mission for your literature review. This will help develop coherence and a sense of where your work is heading.

The writing process may be structured. The list below shows one way this can be done.

Make piles/lists of articles you have read - these will be your sub sections;

Draw a map or diagram of the relationship between all sub sections - this provides the logical flow;

Summarize main points arising from each sub section - these are headings within sub sections;

List the major points form each paper, go back and re-read the articles and note the main points - these are the issues;

Obtain feedback from your supervisor at this stage, to make sure you are on the right track.

A search of Web sites from Australian universities which offer an honours thesis program in information technology, revealed some common problems and pitfalls in the research process, for students working in computing and information systems research areas.

the thesis topic is too broad

the student tries to combine full-time work with research

the student does not maintain the agreed work schedule and therefore submits large quantities of marginal quality work late

the student exhibits poor English expression, writing style and spelling

the student expects the supervisor to do the work

the student experiences difficulties which are not addressed early enough.

Organisations like New Zealand's National Advisory Committee on Computing Qualifications (NACCQ) and the Australian Computer Society (ACS) desire those who are involved in teaching computing courses to stress that the information and communications technology (ICT) profession is a 'people-oriented' profession, not just 'technically-oriented'.

In trying to determine the tasks of research, a checklist is handy for both students and supervisors, in helping to identify a topic or area of interest, as well as the responsibilities.

finding a supervisor to supervise my work in the chosen area

preparing a thesis proposal

reporting on my progress as required

maintaining my progress as per thesis proposal and project plan

negotiating alterations to the thesis proposal and project plan with the supervisor

meeting regularly with my supervisor(s) to discuss progress

ensuring that language, writing style and presentation of submitted work satisfies the institution’s requirements.

Revise the priorities in your time management plan to eliminate the 'time bandits' in your life. I started to work on research on weekends, but I knew that was not enough. The university or college may have some time release plans such as marking assistance or study leave, - so asked. In my case, I took some funding for time release from marking and some research (but the money ran out). Then a special committee gave me some study leave. However you find the extra time to do your research, the return on investment (ROI) for the institution and your professional development is very sound. Professor Frank Vanclay once told me: 'be prepared to invest in your own research as the return on your investment is very good'.

I knew I had to devise 'working smarter' strategies, methods and efficiencies in order to help make research 'work for me'. Here are some ideas I had.

The first idea I had was not original but powerful. It was make my teaching my research and vice versa. I made the boundaries fuzzy and called it a learning journey. NACCQ, ACS and other organizations (for example , Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education- ASCILITE) flourish by riding and nurturing the wave of research into the professional practice of the ICT profession. In my case, that fuzzy approach was through the use of ICT in education (Eustace, 1998). So take your research domain such as networking, e-commerce, spatial information technology or computer ethics and security and connect it closely to your own professional practice, now and in the future. You can start to blur the edges of your teaching and research by looking at the way research is done in other professions. In education and health, for example, much research is targeted at moving the profession forward, by use of the action research method, where you examine your own professional practice.

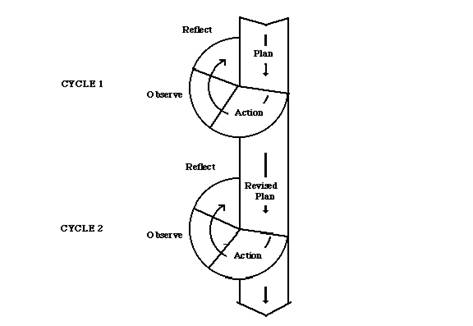

Action researching your own professional practice as a lecturer, brings together the Gemini twins of teaching and research. One useful action research approach is to take a learning journey and take a closer look at yourself by starting to plan, act, observe, reflect, on your own practice, as both teacher and researcher.

Plan, act, observe, reflect are the main stages in each cycle of the action research iteration. The action research approach I used is based on the 'Deakin' model, supported by Kemmis & McTaggart (1990) and illustrated in Figure 5:

Figure 5. Action research protocol after Kemmis & McTaggart

The use of multiple methods, such as action research and ethnography (with interviews, focus groups, content and discourse analysis), is a form of triangulation of research methods, which:

maximises the validity of results,

allows for replication of results in different problem domains.

Replication then provides:

generalisation and reliability for your results.

All artefacts are examined in a manner consistent with the Deakin action research model. Action research includes self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants to improve the rationality and justice of:

our own social, educational practices,

our understanding of these practices,

the situations in which the practices are carried out.

The research experiences here are not the full story, but the issues and techniques discussed in this paper may help research work better for you, as you attempt to do research with full-time work. This can be done by:

making careful choices with the research field,

devising a research proposal plan that uses ethical guidelines and proper project management techniques

using the literature review as a tool to extract the gap, refine and focus the thesis,

finding worthwhile, efficient research methods for data collection and analysis.

I hope that paper helps research work for you by greater acceptance of the responsibilities, by reading widely what others have done and in doing so, avoiding the many pitfalls, with your supervisors to guide you along the road to completion.

Association for Information Systems (2003) Association for Information Systems Web site, Accessed 6 July 2003. <http://www.aisnet.org/>

Brown, R. (1995). 'The "big picture" about managing the writing process', in Quality in Postgraduate Education - Issues and Processes, ed. O. Zuber-Skerritt, Kogan Page, Sydney.

Eustace, K. (1998). Ethnographic study of a virtual learning community. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy. 1998. Vol. 8 Number 1, 83-84.

Eustace, K. & Dunn, A. (1999). Thesis writing workshop report. Thesis Writing Workshop. 13-14 March 1999. Centre for Professional Development, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst. Accessed 15 March, 2003. <http://ispg.csu.edu.au/members/keustace/thesis-writing>

Myers, M. D. (2003a). Qualitative Research in Information Systems . Accessed 6 July 2003. <http://www.qual.auckland.ac.nz/>

Myers, M. D. (2003b). The Web site of Michael D. Myers. Accessed 6 July 2003. <http://www.qual.auckland.ac.nz/MDMyers/index.htm>

Robinson, A. (1999). Critical literature review. Thesis Writing Workshop. 13-14 March 1999. Centre for Professional Development, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst.

Kemmis, S. & McTaggart, R. (Eds) (1990). The Action Research Reader 3rd edition Deakin Uni Press Victoria.

Weber, R. (1999). PhD Supervision: A Student-Centred Focus. Presented to Proceedings of the Australian Council of Professors and Heads of Information Systems, September 1999.

Weber, R. (1994). Research Methods in Information Systems: Observations and a Personal View. Presented to Griffith University Research Workshop in Computer Science and Information Systems, June 1994.

Copyright

Ó

[2003] Ken Eustace

The author(s) assign to NACCQ and educational non-profit institutions a

non-exclusive licence to use this document for personal use and in courses

of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this

copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a

non-exclusive licence to NACCQ to publish this document in full on the

World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in printed form within the

Bulletin of Applied Computing and Information Technology. Any other usage

is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

this

issue | home |

back issues index | about

bacit

Copyright

© 2003 NACCQ. All rights reserved.

Individual articles remain the property of the authors.